I set an alarm to wake up early in the morning to get a solid breakfast in and check out Copan Ruinas before it’d be swarmed by the less dedicated (and more flush on time) tourists.

I had the hilarious privilege of taking a tuk-tuk to the site — I really wanted to ride one and I didn’t really feel like having my bike at a tourist-heavy site where people could rummage through my stuff or steal my jacket. I hopped in one in the main square of Copan and we booked it through town.

I think the reckless abandon of tuk-tuk and scooter / small motorbike riders in places like Honduras is a true inspiration. The guy could really ride, and it felt like really lifted a wheel off the ground in some turns. Other tourists might not appreciate the stomach churning ride as much as I did. I thought it was awesome and over far too quickly.

I think the reckless abandon of tuk-tuk and scooter / small motorbike riders in places like Honduras is a true inspiration. The guy could really ride, and it felt like really lifted a wheel off the ground in some turns. Other tourists might not appreciate the stomach churning ride as much as I did. I thought it was awesome and over far too quickly.

The Copan site is a marvelous example of Mayan architecture. While it looks like an overgrown ruin, it was a site of worship from the 5th to 9th century AD. Kind of bizarre to think that as little as 1100 years ago, the site that is now the ruins of Copán was a living city.

At the main site of Copan Ruinas (which is right on the highway as you exit Copan) you pay an entry fee and then walk into the park. Most people opt for a tour, which I’d probably recommend. While there’s signs around that can inform you about what you are looking at, if you’re with a few people the extra background is probably fun to hear about.

I was so early (and had no fixed plans) that I was actually the first person at the site. It was marvelously, splendidly, absolutely empty. I was blissfully alone in what looked like an overgrown Mayan temple site. Or so I assumed. A dreadful roar rang through the jungle trees and smaller birds flew off as the roar increased in ear-piercing intensity.

I assumed it was some god awful jungle predator or perhaps a person being murdered, but it was the combined cries of the scarlet macaws that call the ruins home. Some apparently live in a small fixed home on the perimeter of the site and they’d all flown to the tree that grows out of the top of the largest ruin on the site. Gorgeous creatures to look at, but they make the absolute worst sounds.

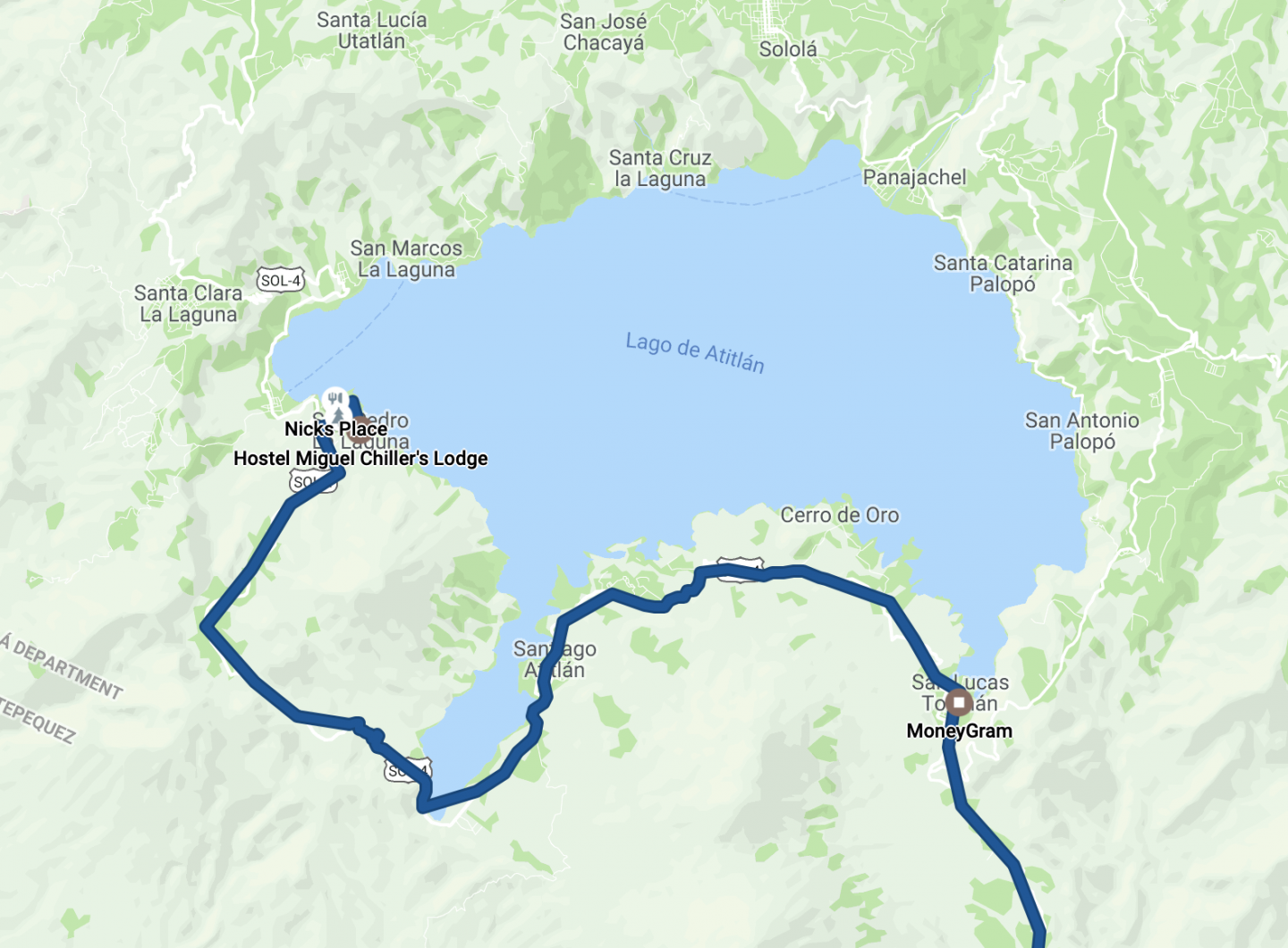

I wandered around the site and really marveled in some of the preserved details and massive scale of it all, with beautiful views of rolling jungle from some parts of the temples, until I left the site in a sort of roundabout way.

It was interesting to fantasize about how differently things could’ve looked if the Mayans had developed their cities in parallel with ours and weren’t destroyed so thoroughly by many factors; Copan, like many other Mayan sites, fell before the Spanish conqueror even appeared.

Some theorize it was because of a catastrophic famine, but there are many theories abound. It’s interesting to think that in a different parallel universe, these temples stand tall, pristine, in the center of a large modern town like the magnificent cathedrals of Europe.

Some theorize it was because of a catastrophic famine, but there are many theories abound. It’s interesting to think that in a different parallel universe, these temples stand tall, pristine, in the center of a large modern town like the magnificent cathedrals of Europe.

That looks out over rolling jungles.

A small walk East of Copan’s main ruins site is a much smaller, still-overgrown site you can visit for a very modest fee. This is a site that is under active investigation and excavation, with small portions of it excavated and visible. It’s fascinating to me to see how people work to excavate and preserve this crucial piece of human history, and I’m happy that even in an exceptionally poor nation like Honduras people seem to understand the gravity of sites like these and the need to protect them. I hope it stays that way.

Next to the site, it’s life as usual.

Who knows what still lies buried beneath the adjacent fields?

It was getting hotter and the sun was rising in the sky, so I decided to grab a tuk-tuk back (weeee!) and ride out. Right after Copan, the highway gets… fun. Dirty and fun.

The truck here didn’t have as much fun as I did.

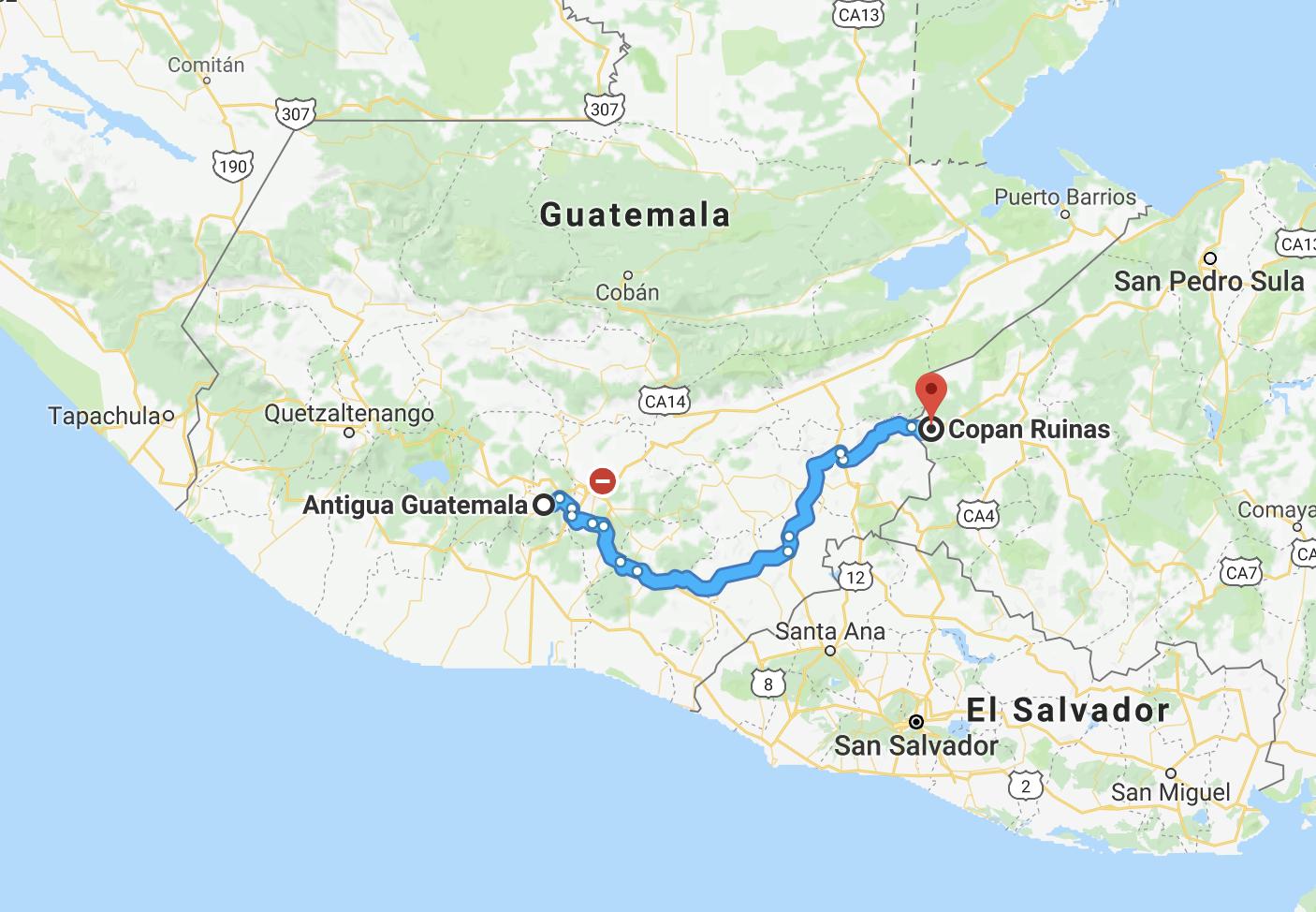

Given my short time and reading a bit about the rather high homicide rates in Honduras, I decided to kind of skip Honduras. Outside of Copan, Honduras does offer some great spots with wonderful nature, great scuba diving and more, but I wanted to get to Nicaragua and take enough time to cross the borders ahead.

I was somewhere halfway in Copan when it finally happened: the cops stopped me on a long stretch of road. Observant readers have have noticed that outside of some military checkpoints in Baja and near Matzlan we haven’t really had any encounters with cops. Many people have horror stories of being extorted or having to bribe their way through countries in Central America, but we’d been spared — so far.

The car appeared in my mirror and flashed its lights. It was an official looking vehicle with some heavily armed military police toting machine guns, so I was cautious but accepted being pulled over. As it happens, around the bend was a checkpoint with a bunch more military police looking types.

I had been making good time across Honduras. Really good time, actually; I was going pretty fast. I enjoyed opening up the throttle on empty and clear stretches, where I could safely use my 1200 cubic centimeters of engine which usually just weighed me down on fun trails.

“Hola amigo!” I yelled, all smiles as I took my helmet off and the cop walked up. He fired off in rapid Spanish: “Do you know how fast you were going?”. I laughed a bit and answered “No, sorry. Is there a problem?”

Some of his friends spilled out of the car and they rapidly surrounded the bike. His friends at the checkpoint had also taken an interest at the scene and were all walking over. I was doing mental math in my head. I wasn’t sure if I had enough cash to pay all of these guys off if they wanted a bribe. And who would I even bribe? I was such a newbie at this stuff. I’d probably screw it up and end up with a mess on my hands.

Without answering my question, the cop asked me “How many CCs?” with a curious look thrown at the cylinders sticking far out my bike. The crowd of seven or so military police was circling my bike like a group of curious sharks. “M- Mille dos ciento!” I said enthusiastically. Twelve hundred! Questions were now being fired at me from all directions. How fast does it go? What brand bike is this? It’s super fast isn’t it? Where are you coming from? What is this? What does this thing (my Spot beacon) do? We chatted a bunch, and it seemed they were all just getting a kick out of this weird gringo on his giant bike. They offered me a cigarette and I declined and asked if I was OK to leave. “Si, si, claro amigo! Buen viaje!”

And with a wave and some laughter from the cops (and a few stickers lighter) I roared off, taking extra care to really rip as I departed. Sometimes your encounters with the police can be fun. I’m sure others have had nightmarish encounters, but I felt like my friendliness and being utterly unintimidated probably helped me a bit. The other part that helped was having a fast bike. Fun times!

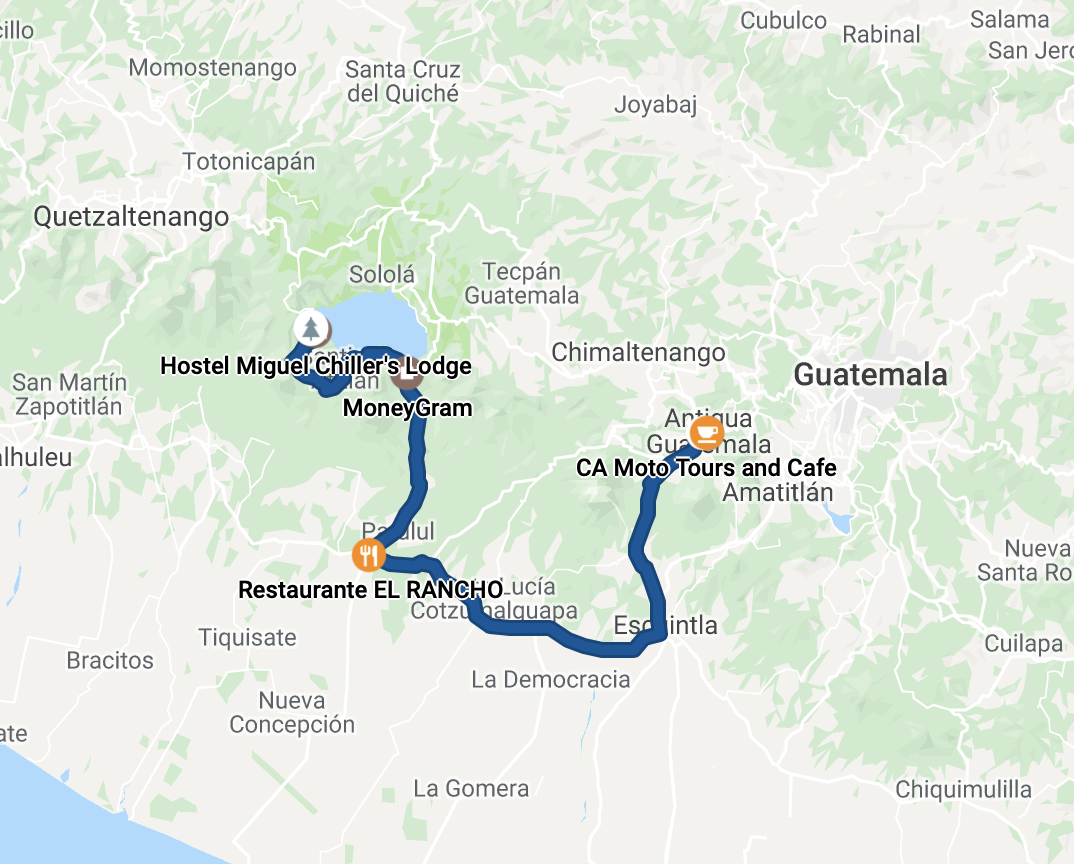

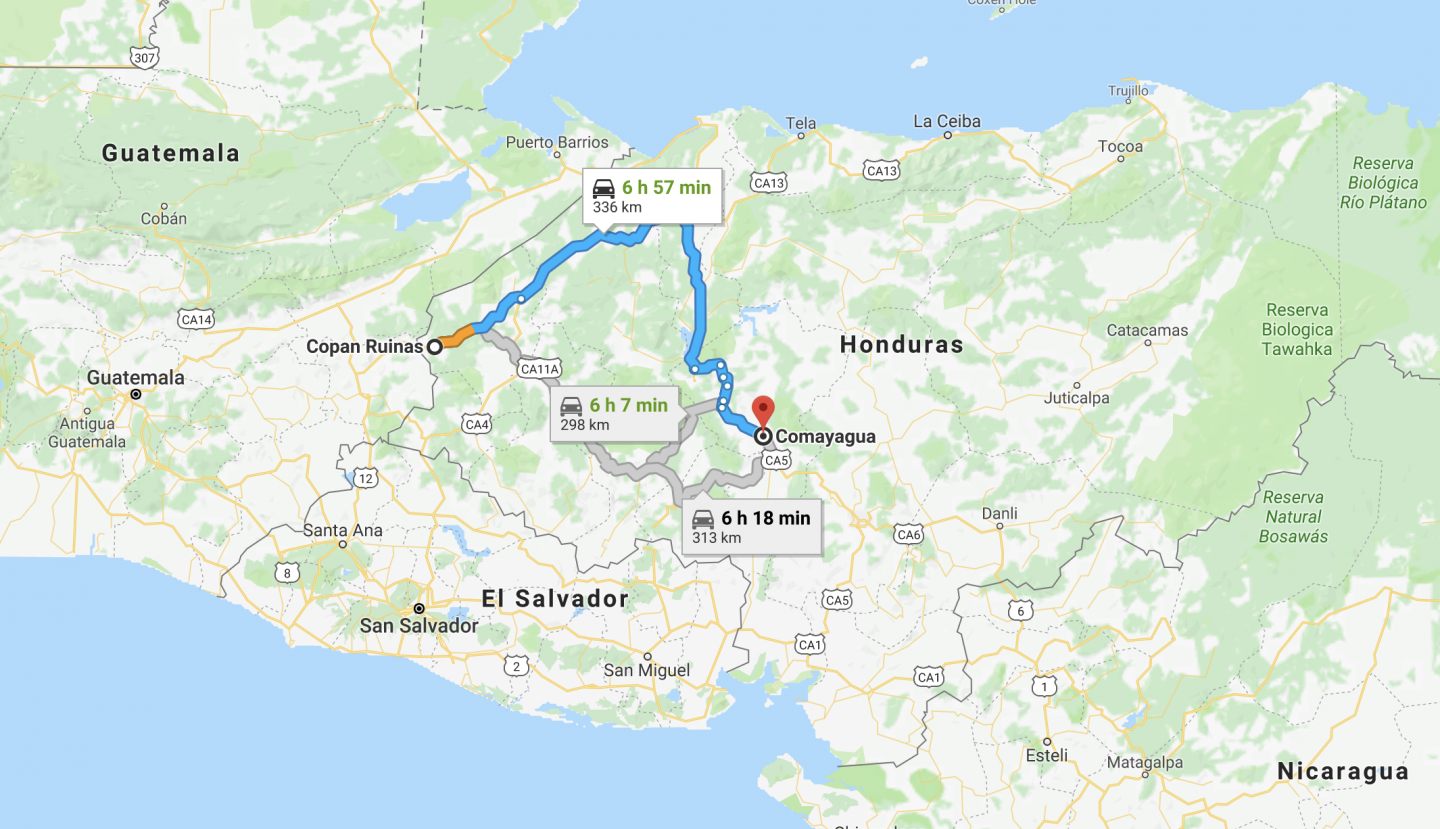

Honduras wasn’t quite as small as I’d assumed, and I was forced to retire my lofty goal of making it across the country in one day as it got dark as I was riding out of a gorgeous mountain pass near Comayagua.

The roadwork had delayed me quite a bit, and I felt tired. I’d gotten in two near-crashes that day, which were my only ones so far, and I felt like I was pushing myself too hard. On top of it all, I was too generous in estimating my progress for the day, so I ended up riding after sundown in a crappy outskirt of a larger town. It was sketchy-feeling, and the gas station attendant told me to get the hell out of that area. After getting a tip from him (a very friendly local) I rode up out of the barrio and found a decent hotel with safe parking near the town square of Comayagua.

I think on any motorcycle trip, regardless of your pace or schedule, you’ll have days where you feel like you’re pushing yourself. It’s entirely OK to do so, but there’s also times where you realize you push yourself too far. For me, this day was one of those days. In an unknown country, which already had many risks, I basically traded more risks for getting somewhere a bit faster. That tradeoff is simply never worth it. Don’t do what I did.

The border was three more hours of riding away. I hit the bed and instantly passed out.

———

Still on the early-morning rhythm of my Copan trip, I woke up nice and early the next day and rode out of town quickly. The road to the border was a quick and easy shot straight across Honduras, and some nice scenic curves spit me right out near an absolutely massive procession of trucks that probably went on for miles.

When I run into traffic like this at a border, I just ride up past them. Trucks and other traffic usually gets a different type of treatment than ridiculous motorcycle touring gringos, and if they don’t they’ll tell you in no uncertain terms. My assumption was correct.

The Honduras/Nicaragua border is a fairly straightforward affair, but you do have to take some time for it. On the Honduran side, I ran into what must’ve been the biggest pack of ‘helpers’ I’d seen on my trip so far which I had to practically swat off. Once at the passport control, I met a rather unmotivated team of customs and border control people that weren’t spectacularly happy to tell me what to do or how to go about it.

Regardless, after about an hour of talking to various desk jockeys I got myself stamped out of Honduras — less than 48 hours after getting my entry stamp — and I was on my way to Nicaragua.

I met a jolly bunch of helpers on the Nicaraguan side which I only used to find someone to change my Honduran money into something Nicaraguan. For once, I had no data service, so no way to check the exchange rate. I just went with what the guy suggested as a rate and later found out it was surprisingly reasonable.

The basic Central American business is done entering Nicaragua: a ‘quick’ passport stamp (there was a line of perhaps 50 people this time, and they took a break halfway into processing them), and vehicle import work. They once again diligently checked the VIN on my bike and all the paperwork. They made errors three different times on the documents, forcing me to ask them to fix the VIN and my name until it was completely accurate. Never settle for a slight inaccuracy of one character on your document as it can cause a huge headache down the road as you try to exit.

Nicaragua also had me go to a set of tents to get fumigated (well, the bike did…) and to get insurance. With insurance and a fumigation paper I went back to the vehicle import window and they quickly processed my paperwork. “No copias?” I asked, incredulous. No, the customs officer said with a smile; he’d do them himself, no need. That was a first. As he copied the paperwork I snuck a Ride Earth sticker under the window and I rode off.

Thumbs up!

Total time for the border crossing: three hours.

I rode off from the border, grabbing a drink from some friendly merchants who were selling refreshments to the tired truckers trying to make their way into Honduras, and smiled as warm Nicaraguan forest air flowed through my helmet. This was going to be a good country, I could feel it.

He’s a great dude. I wished him the best, we pointed bikes in opposite directions, and off I went.

He’s a great dude. I wished him the best, we pointed bikes in opposite directions, and off I went.